I found several old photographs that I wanted to include in the post I did for my father’s 100th birthday on August 2, but sometime in the move from our old house last year I lost the power cord for my scanner. I ordered a new cord, and I have finally uploaded the scans.

This is my father (he thought) and his mother, in a photo that must have been taken in 1917 or early 1918, not long after his birth. Based on the plants behind them, it must have been warm weather, so probably late summer or early fall of 1917. He was wearing a dress at the time.

The photo was not taken at the house in Rome where my father grew up, so it might be where my grandmother and grandfather lived in the little town of Cave Spring, not far from Rome.

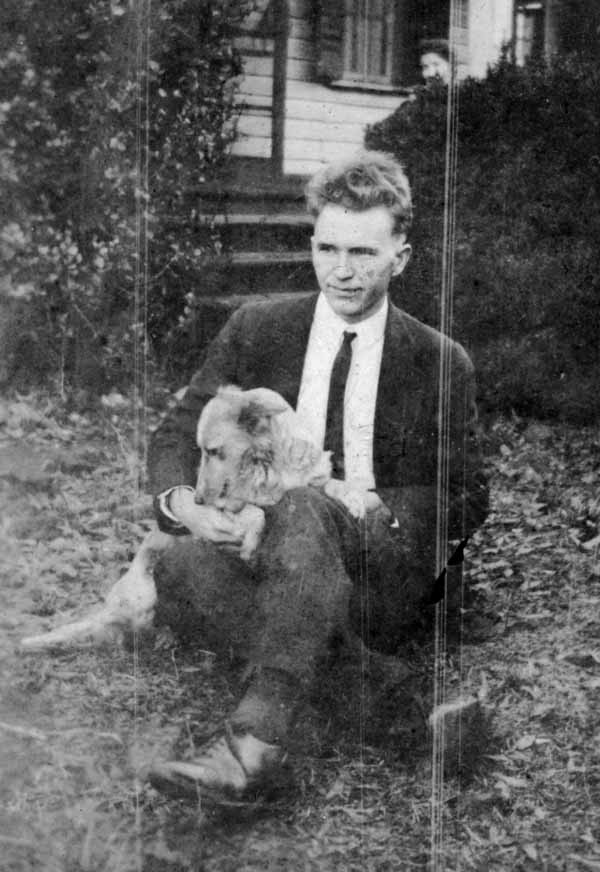

This is a photo of my father’s biological father, who died when my father was so young that he had essentially no memory of him. I can’t remember how he died, but it was from something that does not kill people today.

I don’t see any facial resemblance to my father, except maybe the hairline. Leah thinks he does resemble my father. I can say, though, that I must come from a long line of dog lovers.

This is my father in his uniform wearing a garrison cap.

I’m not sure where this was taken. It might be in the back yard of his home; there was an alley that ran beside the house from 5th Avenue up to what was then Avenue C. I don’t think it was in the front yard on 5th Avenue, because the houses don’t seem to be right. It’s probably just me, but I think the 1940’s Army uniforms look better than the current ones. I think they have more in common with 19th Century uniforms than the later 20th Century uniforms. The boots and trousers look like a horse-back riding uniform. In fact, my father trained in horse-drawn artillery units before the Tiimberwolf Division deployed overseas; of course by the time they reached Europe, the US Army was’t using horses for combat transportation.

This is my father and mother in front of another unknown house. Since both are now gone, there really isn’t anyone to ask where it was taken. He’s wearing a service cap in this photo. He was also wearing a Sam Browne belt, as you can tell by the small buckle in the center of his chest.

This is the “old home place” where my father grew up.

I don’t know when this house was originally constructed, but I believe it was prior to the widespread use of indoor plumbing in Rome, probably in the late 1800’s. The house consists of four rooms, two on each side of a central hall that ran from the front porch to the back porch. I think the house originally had a porch on all four sides. As you can see, the windows were taller than the front door. I think even when this house was built doors were usually the same height as modern doors, which is six feet, eight inches. In modern architecture, the tops of windows and the tops of doors are at the same height. In this house, the windows are higher than the door top and reach all the way to the floor. This was a typical Southern construction method which was intended to help ventilate rooms in the hot, humid summers.

The room layout was probably a living room or parlor and a dining room at the front, and two bedrooms at the rear. I think the house had several significant modifications by the time I came along. A separate apartment was added on the back left side room by enclosing part of the porch. What my father called the sleeping porch was a room that was enclosed on the porch off the back right bedroom. I think it was used as a bedroom during hot weather.

There was a small sitting room on the back rear that was under the porch roof, and a kitchen that I think was at least mostly under the porch roof at the back corner of the house. My grandparents basically lived in the kitchen, sitting room and the back right bedroom. The other rooms were seldom if ever used.

There was a bathroom on the extreme left corner of the house, also under the porch roof, that could be reached only by going out of the sitting room and walking across the porch. It was necessary to go outside to reach this bathroom, although my grandparents put some kind of plastic sheeting on the porch to kind of enclose it.

The structure on the left of the house is an old greenhouse, which I vaguely remember.

This kind of architectural history is interesting to me and probably a few people in the world, but probably not to many others.

My father and at least one of his male relatives weatherproofed an old chicken coop in the back yard and moved their beds out there. One was Uncle Charlie, my father’s maternal uncle, who looked so much like my father that some people occasionally confused the two. The biggest clue to which was which was the fact that Uncle Charlie lost his right arm in an accident.

I also scanned a photo that my father took in Europe when he was there during WW II.

This is actually a contact print. There is some writing on the back that identifies it as a German gun emplacement on Utah Beach in September 1944. Not as busy as it was three months earlier. I wondered where or when my father got this photo processed. I discovered something on the back when I scanned it.

There is a very faint stamp on the back. I can read part of it: “NOT FOR PUBLICATION”, and 5 MAR. I can’t read the year, but it’s probably 1945. I assume from this that it was printed at some Army darkroom in Europe.

After looking at this photo and the photos of my father in uniform, I looked at the Wikipedia entry on the 104th Infantry Division. It’s basically a shortened history of the division, a little easier to follow than the much more highly detailed account in Timberwolf Tracks, the history of the division. I saw place names that my father mentioned in the stories he told us: Camp Adair, Aachen, the Ruhr and the Rhine. For some reason, seeing those names had a stronger emotional impact on me than just looking at the old photos. I can still hear him saying those names.